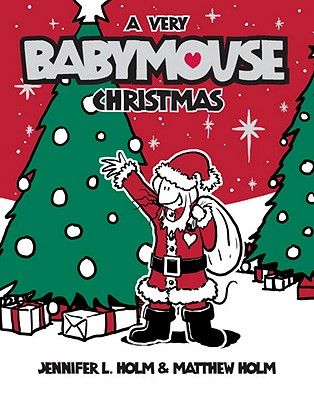

Jennifer L. and Matthew Holm on 20 Years of Babymouse | Interview

It feels like yesterday that I first picked up a copy of Babymouse: Queen of the World. At the time, in the infancy of comics and graphic novels for young readers, I did not fully appreciate the innovative nature of the story. As a young librarian, all I saw was a great story that my students loved. My students were on the “old side” for the book, but they still gravitated toward the spunky mouse who had pizzazz and self-confidence.

Twenty years later, Babymouse remains a staple on library shelves and is prominently displayed in bookstores. On the eve of the 20th anniversary of publication, I had the opportunity to sit down and speak with author/illustrator, brother/sister team, Jennifer L. and Matthew Holm.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Esther Keller: Congratulations on 20 years of Babymouse collaboration. When you started, did you ever imagine you would still be working together with the same character for all these years?

Jennifer L. Holm: No, I mean, I think it’s so crazy, mostly because just trying to convince a children’s publisher to take a risk on a graphic novel for children was such a high hurdle for us to pass at the time for a couple of reasons. One, that there really weren’t any graphic novels for kids then, but also, the publishers didn’t have a pipeline to produce graphic novels. They were used to making 40-page picture books, but to do a 100-page book with art was not really in their bandwagon; there was nowhere to put them on the shelves..

Matthew Holm: Every single place we went would be a different type of shelving. It’s like, well, here it’s with the humor books, here it’s with chapter books. Here it is with Garfield.

Jennifer: Here, we’re not sure where to put it, so…

Esther: Which is very similar to what was happening in the library world. You know, where do we put these graphic novels? Do we pull them out? Do we not pull them out? It’s very different now, but at the time it was just so new. And of course, convincing people that it’s worthwhile reading.

Jennifer: That was probably the biggest hurdle. I feel like the librarians were completely our biggest defenders out of the gate.

Matthew: Oh, yeah.

Jennifer: But I do feel like Matt and I spent a good 10 years on the road evangelizing at schools, to teachers, to parents, that comics are okay. We read them as children, we turned out okay. So, that was, like, a long, slow slog, and then somewhere around 2015, I feel like it exploded, and everybody was like, oh, that’s fine now.

Matthew: I feel like the only thing now is that everyone’s accepted that graphic novels are okay to read, but sometimes they’re like, but not too many, you know?

Esther: I have a daughter in 8th grade, and I remember last year, her teacher was, oh, you can read graphic novels, but no, it can’t be part of your reading log. And then this year, she was told, No, it’s okay to have them in her reading log. It depends on the teacher. Thankfully, it is mostly accepted, but having transferred to a new high school library just about 3 years ago, I feel like I have to start that advocacy again. Whereas, before that, I was in the same middle school for 20 years, so everyone was like, okay, okay, we know, Keller. This is how it’s going to be. Graphic Novels are good.

In preparation for today’s interview, I went back and re-read some of the older Babymouse titles. Babymouse is still as relatable today as she was 20 years ago. I could absolutely see my daughters, one is in 8th grade and the other has started high school, connecting with her insecurities, her humor, her imagination. What do you think it is about Babymouse that makes her timeless for a new generation of readers?

Jennifer: I think why she still connects is that she is still going through, in the books, all those basic things that we forget about when we’re grownups. I’m a mom too, and I just remember the first time my son forgot his lunch, and he came home just hysterical and in tears, and I’m like, it’s just lunch, honey. He’s said, You don’t understand! This was in second grade. And I didn’t understand, because I forgot. You’re right, all these little things that happen for the first time are so life-shaping. It doesn’t matter if it’s 1980 or 2025; if you forget your lunch, or a kid is mean to you, or you’re not invited to a sleepover party, it’s going to hit just as hard.

Matthew: In terms of the problems, yes, all the kids have the same problems, and in terms of why I think Babymouse still has staying power, it’s that she’s wildly optimistic. Unjustifiably optimistic. Even though she does get knocked down, she gets back up, and she is always certain that she can do anything. So, I think that sort of confidence goes along with welcoming people in.

Also, her imagination is just an open door to all sorts of adventures and humor and pop culture, and classic literature. 20 years on, doing school visits, the thing I do most is stand in front of the kids and draw with them original Babymouse Adventures. Where you can have Babymouse be anyone, go anywhere, do anything, what is she doing? And there’s always something that works in the Babymouse universe, with her imagination going wild.

Esther: We already touched on this, about how when Babymouse first launched, graphic novels were very new, and they weren’t so common in school libraries or bookstores. What shifts have you noticed in how educators and parents view comics as tools for literacy and learning?

Matthew: I think one of the things that we’ve seen, and that librarians especially have recognized, way earlier than we even knew it, was that you run into kids who are struggling with reading. Graphic novels, especially a graphic novel like Babymouse, which is right around 100 pages, make it possible to complete a book. Which is something that Jenny and I, who were strong readers, never had a problem doing. We were the nerdy bookworms. But here, kids would come up to us and say, “This is the first book I ever finished,” and they’re in 4th grade, maybe. It just never occurred to us that that would be a thing. Yet, finishing a book gives them so much confidence to try again, because so many of them would start a book, they’d get frustrated, and then they’d stop. Graphic novels like Babymouse, on the other hand, they’re accessible. They’re fun. They don’t seem too intimidating, even though a lot of the content is the same as any other story they’d be reading, in terms of character development and plot.

And a lot of the words, as we know from comics, are often at a higher reading level than in other types of books that are in the same age bracket. So, all these things are sneaking in, but the way that comics are so engaging, readers keep plowing ahead. They have the pictures to help them understand what’s going on. All those little things boost their confidence, making them feel more accomplished, which gets them to read the next book, and the next book, and the next book.

Jennifer: Confidence.

Matthew: Yeah, it’s definitely confidence-building.

Jennifer: Boosters for kids.

Esther: Absolutely. I have a 9-year-old also, and my 9-year-old tells me all the time he hates to read. Except that he’s always on the couch or in bed reading a comic book. Now it’s my running joke, “I know, I know you hate to read.” Yet I often need to pull him away to go to bed or do homework. Maybe he’ll always read comics forever, but it doesn’t matter, because it’s still the printed word. My daughter, who is similar, also used to say she wasn’t a reader. And then one day I told her, you know, comics are actually books. You are reading. When that clicked in her head, suddenly, she would pick up anything. It was almost like she was being told that comics are less. Therefore, she wasn’t a reader. Even though comics are very much a book, and Matthew, like you said, it has all the elements of story, plot development, it has character development. You could analyze it in the same way that you would a novel.

Jennifer: 100%.

Esther: How has Babymouse evolved since her debut, both in how you write her, illustrate her, and how your young readers engage with her today?

Jennifer: Well, you know, she grew up… soft grew up. She didn’t get too old. She went to middle school, and she’s not going to go beyond middle school. Aging Babymouse was kind of a fan, kid-directed, step. Because what would often happen is that kids standing in line at a book signing, with a younger sibling, say an 8-year-old, and the older sibling, who was about 12, said, I used to read Babymouse, I wish there was an older Babymouse for me now. And we thought, hmm.

But I think what the most interesting thing was, in the last 20 years, is that when we first wrote it, in our head, it was solidly for 3rd grade and up. That was our core audience. But it’s picked up so much earlier. We often hear from teachers and librarians that it’s picked up at the end of kindergarten, beginning of first grade. Which was unexpected, but sweet. I think the younger readers don’t get some of the cultural references to Star Wars or whatever we’re homaging, but they get the basics, and then they go back and reread years later. So, I do think it was surprising to us.

Oh, the other surprising thing was, you know, it’s pink, it’s a girl. We assumed that we would just have girl readers. But we have crazy boy fans. I mean, probably the sweetest one I met lately was when I was doing a book signing at a bookstore. The bookseller was a guy in his 20s. He asked for a book to be signed, and I said “Of course!” I asked, “Oh, is this for your little sister?” He said “No, it’s for me. I used to fight with my sister over these books. I’m going to tell her I got one signed, and she didn’t.” It got to the point we had so many boy readers that Matt has a funny t-shirt he used to wear to events that says, It’s not pink, it’s lightish red.

Matthew: Always, always gotta wear the pink.

Jennifer: Yeah, the boys don’t care about the color. It’s funny. That was our own preconceived idea.

Esther: Why did you go with pink?

Jennifer: As much pink as was in the book, our original idea was we were just going to have pink as a little heart on her dress, and maybe the folio page numbers. And then, as we were developing it, we came up with the idea to use a pink wash to reinforce when she’s having a fantasy, so there would be a real visual cue, you go from the boring black and white world to the imaginative color world.

And we could only pick one color, because the possibilities were quite low back then.

Esther: You pointed out that you were strongly targeting girls. In those days, most of the comics were geared to boys.

Matthew: That was the real driver, I think, because Jenny is the only girl in our family with four brothers. We all read comics. She read the same comics we did. And at that time in the early 2000s, all we ever heard was, Oh, girls don’t read comics, you know? At that point, Jenny, you were reading more Marvel DC superhero comics than I was, probably.

Jennifer: Yep.

Matthew: So, it’s definitely a reaction.

Jennifer: The original concept of Babymouse grew out of a frustration with my youth. Like Matt was saying, I grew up in this house full of boys. I read all their comics. Our dad was a huge comic reader. He actually gave us the bound volumes of Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon. I loved all these characters, but there were no girl characters that I related to. I did not relate to Wonder Woman. I’m sorry, I know she’s had a comeback, but, you know, she wore her underwear. It really bothered me as a kind of tomboy girl. And I just longed for there to be a girl character that I could relate to the way my brothers could relate to Peter Parker. It didn’t seem like a big ask, but it was.

Esther: It really shows how we’ve come such a long way in the comics industry.

Jennifer: It’s wild when you look back.

Esther: As a brother–sister creative team, how do your different strengths and personalities shape the stories? Can you describe a moment when you saw things completely differently — and how that made the final book stronger?

Matthew: You know, it’s funny. Everyone says, You’re a brother and sister, you must fight all the time. But growing up, Jenny she’s 6 years older than I am, and there was a brother in between us, in the age ranking. I’m the youngest. And so, Jenny and I never really interacted, frankly, all that much when we were kids.

Jennifer: Yeah, he was the toddler in the playpen in the kitchen that we all ignored. Like, we were never in school together, or on the bus together, or anything, because it was a big age difference.

Matthew: Yeah, so we didn’t really get to know each other. Other than the fact that we were reading the same books. She was stealing my Calvin and Hobbes and Bloom County books, and I was stealing her Dragon Riders of Pern books. I was stealing all her fantasy, and she was stealing my comics. But aside from that, we didn’t really interact and build up the kind of animosity that siblings can have sometimes.

And so, when we get out into the adult world, we didn’t have any of that baggage from our childhood, but also, we both were working in creative industries where we were getting critiqued constantly. I was a writer and editor for Country Living magazine, writing about home decorating and kitchens and things, and I would write a story, and it would get edited by six people and come back to me, and there’d be maybe three words that I wrote originally that survived the edit.

And Jenny was in advertising. She would have to go give five different pitches for commercials, and they’d say, these are all terrible, and they’d tear her to pieces in the meeting. She would then have to go back and pick herself up and come up with five new ideas to pitch. So, we were used to being edited. We were used to people coming in and saying, this isn’t working.

So when we started working together, there wasn’t ever really a point where we were butting heads over anything creatively. The workload on graphic novels is always just so high. The timetables are tight, the amount of artwork that must be produced is tremendous. And when we started Babymouse, we had four books that they wanted to put out within about two years, maybe a year and a half. That’s a lot. A lot of writing, a lot of art to do.

And so, it really was just expediency and sort of our training and personalities of just being able to say, “this isn’t working, let’s change it to this.” And the other person would say, “you know, you’re probably right.” You’re seeing this as the reader might see it at first glance, so let’s just go with your thought. So, over and over again, on these books, we’d have a change on something, and the other one would say, that’s not working, can you change that? Like, oh yeah, sure, I’ll do that. We didn’t really have a moment where we clashed, and we had to come up with something new. It was more just like, quick fix that, quick fix that.

Jennifer: I think one thing that happened that was funny that changed the creative way that the books went in the early drafts… it was pre-internet, I mean, we had the internet. It was the late 90s.

Matthew: But we didn’t have scanners. We didn’t scan.

Jennifer: So, when we work, we work long distance, we scan art and send it back and forth, but in the early layouts, we’d be FedExing paper copies back and forth to each other. I would do the layout and then send Matt my layouts. Matt’s very snarky, so he would just go through and make little arrows and start making snarky comments, like, good luck, Babymouse. I don’t know about that, Babymouse, and all those little snarky things, that became the narrator. Like, his funny comments eventually became the narrator, who then became, in my head, having a British voice.

Esther: Teachers and librarians often say Babymouse is a “gateway series” for reluctant readers. How intentional was that aspect of accessibility — and what advice would you give to adults who want to nurture a love of reading in every child?

Jennifer: It was very intentional when we did it, because I feel like I grew up learning how to read by reading comics. One of my best friends was originally from Puerto Rico but grew up in the Bronx. We met when we were in our 20s, and he always said that he learned how to speak English by reading Superman, and that always stuck in my head. I’m like, oh yeah, me too.

Esther: A lot of people have said that to me too.

Jennifer: Basically, comics diagram sentences. It’s really easy when you think about it. But I think what we’ve really noticed lately with this generation of kids, certainly with my own kids who are now grown up, but when they were kids, is they are so easily discouraged, this generation. They don’t have the moxie of us old people, you know? They get crushed super easily, and so I think, having a book like Babymouse, where they can finish it and feel confident, helps them to kind of push forward.

Matthew: We knew it was going to be a gateway book, and I think that was in our early pitches and our early discussions when we were working on the start of Babymouse.

While we were writing and drawing, we spent about two years before the book even came out talking to librarians and booksellers about what this was and what you could do with it, recounting the fact that, yeah, we grew up reading this way. We grew up learning how to read comics and then read other books.

And I still have discussions sometimes when I go to schools and meet with teachers and parents. I tell them, our dad grew up reading comics and loving comics, and he became a doctor, you know, so it’s okay, you can read comics and read other things, and you’re going to turn out okay.

Also, my experience growing up was reading the little collections of Charlie Brown and Snoopy, or getting the Marvel and DC comics that were, like, 25 cents at the newsstand, you know? Part of the idea of Babymouse also is that it would be a sort of a compact book you could take around with you, read by yourself.

Jennifer: Inexpensive.

Matthew: And inexpensive. I still hear that. I was at an event last spring in Pittsburgh. It was a big conference, and a bunch of schools were bussed in. The teacher librarians said they were so glad that there are still books like Babymouse, because a lot of these kids can’t afford to buy new books that are coming out now with cover prices that are about $25 a pop. Whereas Babymouse is very, still very accessible.

[As an aside: I went back to look, and a volume is typically $6.99. Wow! Most graphic novels are a minimum of $9.99.]

Esther: Absolutely. Which is also why it’s so important to have libraries.

Matthew: Yes. I lived in Portland, Oregon, for many years, and there were a lot of schools I would go to out there that did not have a librarian, or they had one librarian covering 11 elementary schools, which, even if you’re going to two a day, you can’t get to them all in one week.

Esther: Fortunately, there are strides being made, just not enough, and not fast enough.

Jennifer: I know.

Esther: Many of your readers have grown up with Babymouse. How do you approach writing to the new generation that’s changed so much? You know, they’re surrounded by digital media, visual storytelling, and new expectations of representation.

Matthew: Well, one thing that I think has been interesting is that when talking about Babymouse in schools to kids and teachers, we realize that graphic novels are kind of part of the prep for the new visual world that everyone is living in. Kids may not, in their life anymore, need to write outside of college. Even a long letter to someone, certainly not on paper. They might not find themselves in a situation where they’re writing tens of pages of paragraphs for any given assignment, at their job, or a letter to communicate something to someone.

But what they are almost certainly going to have to do, even before they’re out of high school, is make a PowerPoint. Which is all about arranging visual information, and how you do the hierarchy on the page, on the screen, and how you have these different elements working with each other. What does the person who’s reading it want to read first?

One of the reasons I became a comics artist is because I read so many comics as a kid, and just like when you read fantasy novels, or romance novels, or murder mysteries, you sort of internalize what the format is all about, so it’s second nature when you’re going to tell your own story that way. I have a sort of intuitive idea of how comics work and how to place panels and all that sort of stuff.

Kids are going to be getting that same thing. They’re reading these comics, they’re boosting their sort of internal visual knowledge, and then when they have to go make those PowerPoints, make those apps and web pages and whatever else is coming next that we don’t even know about technology-wise, we know there’s always going to be a strong visual element to it. So, I think it’s been surprising how much that’s really eased right into preparing them for the world as it has grown around us.

Jennifer: What was shocking to me as a mom of a recent high school grad was how much Millie had to, starting in middle school, do these Canva and PowerPoints and Google Slides. They were her reports every time. Her group projects. I was like, this is a whole new world, and I can’t help you with this.

Esther: I always wonder, is it because the teachers don’t want to grade 1,000 essays? But it does really prepare them. I go back and forth. I want students to be able to write a paragraph when they graduate high school, but at the same time, the reality is that it’s such a visual society today, and they need to be able to interpret visual material so that they can critically think about the visual material, not just the word.

Can you walk us through your creative process from idea to finished book? Do the words come first or the pictures come first, or is it, like, a conversation between you as you build a story?

Matthew: We both sort of come up with the initial ideas. We’ll say, “Hey, what do we want to do for the next book?” Especially when we were in the thick of making Babymouse. We were doing two, three, four books a year, especially between Babymouse and Squished. We’d say, “What is this one about?” We might say it’s about puppy love, or Babymouse skater girl. We’ll start riffing ideas off on that. What would be fun things, what are things we remember from when we were kids, funny things that happened to us. Maybe terrible things that happened to us, but in retrospect, and with time, you can make them funny.

And so, we’ll sort of spitball those. Jenny will take notes. Of course, with Babymouse, she has the fantasy sequences, so then we have to try to make sure we’re coming up with original ones we haven’t done before.

Then Jenny goes off and she writes the manuscript. We have always liked to work over this written story first as much as possible, and make sure that that’s really working from start to finish, because it is a lot easier to change a story when it’s just typed out than it is to change artwork after I’ve drawn it. For example, if Jenny says, imagine she goes to the moon, and there’s a moon city full of thousands of aliens, and I have to draw thousands of aliens. It’s easier to just have her say, like, no, she’s not going there, she’s going to Cleveland. We do that first, and then, we send it to our editors, our editors have their input, we get it back and do a new round of revisions.

And then I’ll start doing sketches based on the story. And I don’t do detailed sketches. I don’t even think about what the whole page is going to look like. I just do individual shots, like, individual panels almost, moment by moment from the story. Just trying to get my ideas down on paper as quickly as possible. Sometimes the stuff will look almost like stick figures, and if I mess up, I’ll cross it out and make notes to Jenny. And then I’ll scan those sketchbooks into the computer, send them to Jenny, and then Jenny, why don’t you talk about how you do our layouts?

Jennifer: We have a very unconventional creative relationship. I haven’t met any other writer/illustrator team that works like this. Usually, the writer and the illustrator are kept far away from each other, but there’s so much work and there’s just two of us.

So, he’ll send me all the art, and I’ll print it out, and then I’ll cut and get sticky glue, and I’ll lay it out the way it’s going to look as a two-page spread. I’ll do that for the whole book, and then I’ll scan it back to Matt, and he uses my layouts as the tracing layer for the final book.

Matthew Holm: My sketches I do in pencil on paper, and just in a sketchbook really fast, but my final art I do in Photoshop on the computer, using a drawing tablet with a special drawing stylus. I’ll use her layouts as the tracing guide, I’ll draw over that and do the inks, and then for Babymouse, I would also then go in and do a layer of the pink for wherever that’s showing up in her daydreams.

That’s kind of how the whole thing would work out. Nowadays it’s a much more colorful world in publishing, and so at the coloring stage, we’ll hand it off from my black and white drawings to a colorist whose entire job is just to color in the book, and which is, you know, a huge weight off of me, because aside from figuring out where the pink goes, color has never really been my forte as an illustrator, and it’s just, again, that’s another entire job. That’s months of work on its own.

Esther: Oh, wow. Though I know many graphic novels have a separate colorist, I never realized how long the process took! It’s a fascinating process in general. With all the years that I’ve been reading, evaluating, and reviewing graphic novels, I’ve been more and more fascinated with the process. And I see a lot of my students constantly drawing.

Matthew: That’s the thing we always talk about when we go into schools, because we always run into kids that come up to us with their own comics that they’ve made.

What is so great about creating comics is that they are broadly collaborative. Most comics are made with multiple people on board. Which is helpful from a writer’s block standpoint. Because if you get stuck, you can always go to someone else and try to get their ideas on things. It also makes it more fun, because it’s more like play, instead of, just sitting there, grinding away, working by yourself writing something. You’re bouncing ideas off each other, you’re trying to make the other person laugh if you’re doing a funny comic.

We always tell the kids we see at schools that you can work on a comic with someone else, and if you don’t feel confident in your own drawing skills, find someone who really loves drawing, let them do the drawing, and then you can do the writing. We’ve been to schools where kids have come up to us and said: “I’m the artist,” and “I’m the writer.” Or “I’m the manager.” They have an editor-publisher who’s trying to figure out how to sell it to their classmates and things.

Jennifer: “I’m the agent.”

Esther: Last question: As you celebrate two decades of Babymouse, what’s next for her [Babymouse] and you? Are there themes or projects you’re excited to explore in the next chapter?

Jennifer: Well, we are mostly excited right now that she’s coming out in full color. She’s going from her quiet, black-and-white era of, like, the 70s to full color in 2000s. We’ve been working together for almost 25 years, since we actually started working on Babymouse back in 2001, and for our next project we are embarking on collaborating on our first middle-grade novel. It’s the first time I’ve ever written a novel with somebody else, and it’s so much easier when you have a buddy.

Esther: That’s amazing. I can’t wait to read that. Even though I’ve jumped to high school from middle school, middle grade novels are still my favorite. I keep going back to read those. And since I work with many ENL [English as a new language] students, I tell myself it’s okay, I can still read middle school, because it fits my students’ need.

Jennifer: I love that.

Matthew: That was always the great thing with graphic novels, and with Babymouse, is that they have such a broad age range of enthusiasm, and for some reason, that it’s acceptable at such a broad age range. So, we would see kids in fifth grade who might only have a first-grade reading level reading the books, and all their peers are also reading it, so they don’t feel singled out that they’re reading a baby book.

Esther: Exactly!

What I noticed during the interview is how much of a team Jennifer and Matt are. They’re almost like two halves of a whole. After growing up together in the same home and collaborating on so many projects for so many years, they bounce off each other so easily. Wishing this dynamite duo another 25 years together to collaborate and bring much joy to children and adults.

Filed under: All Ages, Graphic Novels, Interviews

About Esther Keller

Esther Keller is the librarian at William E. Grady CTE HS in Brooklyn, NY. In addition, she curates the Graphic Novel collection for the NYC DOE Citywide Digital Library. She started her career at the Brooklyn Public Library and later jumped ship to the school system so she could have summer vacation and a job that would align with a growing family's schedule. On the side, she is a mother of 4 and regularly reviews for SLJ. In her past life, she served on the Great Graphic Novels for Teens Committee, where she solidified her love and dedication to comics.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Rebecca Stead’s EXPERIMENT

31 Days, 31 Lists: 2025 Books with a Message (Social & Emotional Learning)

From Policy Ask to Public Voice: Five Layers of Writing to Advance School Library Policy

Where Recipe Meets Magic, a guest post by Marisa Churchill

ADVERTISEMENT